Anyone with a few skills can now make a website that looks like a global corporate.

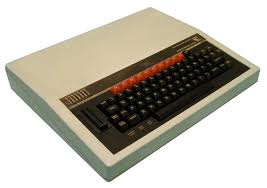

I’ve seen several activities and professions confront digitalisation. When I started at the BBC, computers were expensive and required a lot of knowledge to operate. In the 1980s we used BBC micros to automate several time consuming operations to make animated computer graphics, until the IBM PC took over. This was a process of computerisation and was not very disruptive - it was not really accessible to many. Adequate knowledge and skills were quite hard to acquire. We needed the expertise of broadcast engineers And we didn’t dream in digital yet.

I’ve seen several activities and professions confront digitalisation. When I started at the BBC, computers were expensive and required a lot of knowledge to operate. In the 1980s we used BBC micros to automate several time consuming operations to make animated computer graphics, until the IBM PC took over. This was a process of computerisation and was not very disruptive - it was not really accessible to many. Adequate knowledge and skills were quite hard to acquire. We needed the expertise of broadcast engineers And we didn’t dream in digital yet.

Moore’s Law has allowed ever smaller processors to take over analogue processes. As time has gone by, the spread of computers into just about everything has forced many activities to a digital domain; now they have become digitalised. In broadcast, giant videotape machines began to get smaller, smarter and contained computers. By 1980 there were machines that no longer required a highly trained engineer to operate them. Film editors, confronting the move to video tape and the initial reduction in options, began to cry out in protest: “I have spent my career working on silver, I see no reason to convert to rust!”.

Moore’s Law has allowed ever smaller processors to take over analogue processes. As time has gone by, the spread of computers into just about everything has forced many activities to a digital domain; now they have become digitalised. In broadcast, giant videotape machines began to get smaller, smarter and contained computers. By 1980 there were machines that no longer required a highly trained engineer to operate them. Film editors, confronting the move to video tape and the initial reduction in options, began to cry out in protest: “I have spent my career working on silver, I see no reason to convert to rust!”.

In the early 90s, desktop publishing appeared on computers with word processors, and secretaries began to demonstrate the need for a degree in graphic design if you are going to do it properly. Traditional graphic designers began to sweat whilst artworkers learned to operate systems like Quark and Pagemaker etc. Luddites everywhere consigned themselves to history. The bedrooms of youth began to get computerised. It started with games.

Meanwhile, camera manufacturers were developing better and cheaper video sensors and began integrating smarter processors. Cameras changed and the workflow was complemented by capable digital edit systems, which started to appear in broadcast edit departments. By the end of the 90s, equipment began to plummet in price. In a very few years, almost anyone could afford a digital camera and a computer powerful enough to edit with.

Meanwhile, camera manufacturers were developing better and cheaper video sensors and began integrating smarter processors. Cameras changed and the workflow was complemented by capable digital edit systems, which started to appear in broadcast edit departments. By the end of the 90s, equipment began to plummet in price. In a very few years, almost anyone could afford a digital camera and a computer powerful enough to edit with.

Business began to feel increasing impact. Ever cheaper digital communication and transport, in the form of the Internet, has rendered traditional centralisation less relevant for many industries. Look at how the financial sector has changed. As barriers to entry drop so many benefits of being gatekeepers evaporate. Pressure to decentralise increased. Universities ran increasingly popular trade training thinly disguised as degrees producing an oversupply of labour in the process. The gatekeepers pretty much stopped in-career training.

In the mid-90s I had run away to sea. I spent some time as a race yacht navigator and delivery skipper - until all the money had gone that is. And here too the effects of computerisation and digitalisation were being felt. Decca Navigator had become pervasive as prices of receivers dropped and their capability increased. Navigation software began to appear and laptops won their place on chart tables. Charts were digitised and other yacht instruments became integrated with computers. Navigators began to believe to three decimal places the calculations of machines.

In the mid-90s I had run away to sea. I spent some time as a race yacht navigator and delivery skipper - until all the money had gone that is. And here too the effects of computerisation and digitalisation were being felt. Decca Navigator had become pervasive as prices of receivers dropped and their capability increased. Navigation software began to appear and laptops won their place on chart tables. Charts were digitised and other yacht instruments became integrated with computers. Navigators began to believe to three decimal places the calculations of machines.

Commercial marine was a little behind the curve, but as soon as GPS became globally available for free then ship navigation, like that of land and aviation, became the domain of black box systems that we use without question. Surprise was everywhere, lorries began to get stuck under low bridges, ships and yachts ran aground on things that only high resolution charts could warn them about. Digital has a downside too, it can’t extrapolate stuff - yet.

Commercial marine was a little behind the curve, but as soon as GPS became globally available for free then ship navigation, like that of land and aviation, became the domain of black box systems that we use without question. Surprise was everywhere, lorries began to get stuck under low bridges, ships and yachts ran aground on things that only high resolution charts could warn them about. Digital has a downside too, it can’t extrapolate stuff - yet.

The technology is wonderful, empowering even. But the downsides need addressing. Online graphics are superb, but online typography is often not. The craft skills of typography takes years to master. And generally, some skills and experience are needed to direct the digital artisan.

The technology is wonderful, empowering even. But the downsides need addressing. Online graphics are superb, but online typography is often not. The craft skills of typography takes years to master. And generally, some skills and experience are needed to direct the digital artisan.

To be a good designer the ability to draw analytically, by hand, on paper is actually vital. It shows you can draw what you see in front of you. If you can do that then you can draw what is in your mind. If you can’t communicate what you see in front of you then how can you demonstrate that you actually visualise a solution? Is that solution simply a serendipity of playing with a digital tool?

The bedrooms of youth are now very technological. They are decentralised factories fronted by glitzy websites that give an erroneous impression. Consider this: modern cameras can produce very pretty video almost by themselves. Edit systems are simple to operate too. The traditional filmmaking is a lot more than operating a camera and an edit software. What often gets left out in all this creative democratisation are the basics. In the case of video the ‘creative’ effort is put into the acquisition of pretty pictures and to cut them to music along with almost voyeuristic emotion. Even Hollywood makes nonsense films. The single most common point of failure in all this is simple - the story.

The bedrooms of youth are now very technological. They are decentralised factories fronted by glitzy websites that give an erroneous impression. Consider this: modern cameras can produce very pretty video almost by themselves. Edit systems are simple to operate too. The traditional filmmaking is a lot more than operating a camera and an edit software. What often gets left out in all this creative democratisation are the basics. In the case of video the ‘creative’ effort is put into the acquisition of pretty pictures and to cut them to music along with almost voyeuristic emotion. Even Hollywood makes nonsense films. The single most common point of failure in all this is simple - the story.

In the rush to make a film almost any script will do. The burgeoning deluge of short films - for which there is no market I might add - demonstrate an accent on emotion and shallow depth of field. All driven by nothing. These are a victory of style over substance, something to which Holly, and the other woods, are not immune.

When I worked for the BBC in the 70s and 80s I was aware of no brand, at least from inside the corporation. There were several internal production companies, feral by nature, that were largely trusted to get on with having and implementing good ideas. Management's job was to facilitate them. Excellence resulted from this self policing system.

As years went by so accountants started to look at value along the single dimension of money. Idiotic practises like total costing meant it was cheaper to buy a CD on the high street than to hire it from the internal record library. And some of us thought the BBC had become less of a great place to work. My point is that agile collaborative groups with high standards can turn barely sufficient resources into excellent products. When behemoths own value chains they are driven by different rules and tend towards letting ratings dictate the output. This produces a feedback loop in which more of the same replaces innovations.

I see evidence of groups that are emerging on the Internet of a new and potentially fertile ground for linking different creative perspectives and skills into collaborations that will revitalise a content landscape that has become lacklustre and at best a victory of style over substance.

Recommended Links

Comments